These graphics, made available by the Sixties Project, are copyright (c) 1991 by the Author or by Viet Nam Generation, Inc., all rights reserved. This text may be used, printed, and archived in accordance with the Fair Use provisions of U.S. Copyright law. This text may not be archived, printed, or redistributed in any form for a fee, without the consent of the copyright holder. This notice must accompany any redistribution of the text. The Sixties Project, sponsored by Viet Nam Generation Inc. and the Institute of Advanced Technology in the Humanities at the University of Virginia at Charlottesville, is a collective of humanities scholars working together on the Internet to use electronic resources to provide routes of collaboration and make available primary and secondary sources for researchers, students, teachers, writers and librarians interested in the 1960s.

Say the name aloud of our new Ancestor, Julian Bond, and generations of black Americans will think of a clear, proud voice.

For some, they hear the sophisticated trumpet for justice as a leader of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, the rabble-rousing, hell-raising Civil Rights organization that pushed Martin Luther King, Jr. into militancy and, eventually after Bond left it, catapulted blacks into the Black Power Movement.

For another generation, the name recalls another voice: The baritone narrator of both parts of PBS’sEyes on the Prize documentary series, then and now the definitive television narrative on the Civil Rights Movement.

Few will recall, however, that his voice also extended to the world of 1967 independent comic books.

While issues of The Fantastic Four comic book was over-crowded with science-fiction characters and Peter Parker was beginning to think seriously about Gwen Stacy in the Amazing Spider-Man, Bond, who has just gotten kicked out of the Georgia House of Representatives for his opposition to the Vietnam War, put his real-world thoughts down on picture-filled paper. The pictures were supplied by artist T.G. Lewis.

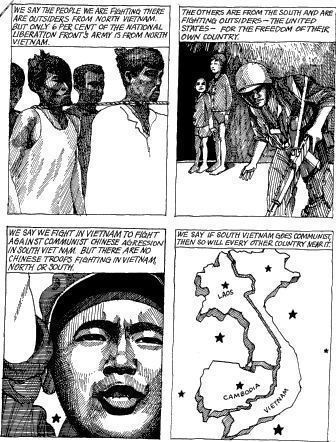

The comic magazine was called, simply, Vietnam.

Its words and pictures merged when black anger and blood flowed freely in American cities likeNewark and Detroit. National black insurrection, if not revolution, would move from the fanciful to the edge of tangible reality.

Americans had gotten used to seeing blood: it came close-up, from dying American soldiers inVietnam on their television newscasts every night, right before they could be rescued into the mostly bloodless dream states provided by NBC’s I Spy or Star Trek or ABC’s Batman. With rioting in its cities, the blood came too close for their denial or indifference—from the nation’s streets, outside its windows.

The 20-page, black-and-white comic book (the cover seems lost; so 19 pages are available online) begins with listing all of the black American leaders—from King to Adam Clayton Powell Jr.—who opposed the war in Vietnam.

Then Bond summarizes what he feels is the average black man’s view in 1967: that the fight for democracy was here in America, not in Southeast Asia.

“One out of every ten young men in America is a Negro,” Bond writes. “But two out of every five men killed in Vietnam is a Negro.”

Bond points out that while blacks were fighting in the Civil War for their right to not be enslaved, the French were fighting to colonize Vietnam.

Bond’s telling of history sounds familiar today: As the United States is prone to do, it set up as Vietnam president its own hand-picked leader, Ngo Dinh Diem, who was ruthless. The Vietnamese response to Diem’s brutal leadership was the creation of a revolutionary organization, the National Liberation Front. “Some people here called it the ‘Viet Cong’ the way some people like people who don’t like Negroes call us ‘niggers,’” the former SNCC leader writes.The civil rights leader discusses the rise of Vietnamese leader Ho Chi Minh (who had become a role model for members of a new, militant black organization, the Black Panther Party), and how Chi Minh fought back when the French tried to colonize Vietnam again after World War II. Meanwhile, Bond narrates, the United States supported the French and later took over that nation’s colonial role under the guise of stopping the spread of Communism.

In his comic, Bond asks the black community to make up its own collective mind about what American interests should be—whether a country founded on revolution and the seizing of other people’s land should choose governments for other nations or work on fixing its own significant problems.

U.S. Rep. John Lewis (D-Ga.), Bond’s friend in SNCC (and his 1986 rival for the congressional seat in Georgia), now has two graphic novels out recalling his life in the Movement. He is the telling story of a happy warrior working to expand American democracy to its second-class citizens.

But Bond’s nationalistic anger, frozen in time and ink, show how angry were the times.

No comments:

Post a Comment